Japanese post-war avant-garde: How a group of Japanese artists redefined what art is and could be

Japanese post-war art is rooted in the rich cultural background of a region that remained largely isolated until the end of the 19th century when the West looked at Japanese art for inspiration and when Japanese artists started to question the visual elements that shaped the region’s identity. This redefinition reached unseen heights in the years that followed World War II when a wide variety of avant-garde movements developed in Japan and many Japanese artists exchanged ideas with their international peers. In this post, we explore some of the post-war art movements and groups that defined the course that Japanese contemporary art took.

The redefinition of Japanese art after World War II

Most scholars identify World War II as the critical turning point for Japanese art. After the war, Japanese artists shifted their interest from surrealism and other modernist forms of imagery to experimental mediums that rejected traditional styles and paved the way for the emergence of contemporary art manifestations. As Doryun Chong, Chief Curator of M+, once shared with ARTnews, the years following World War II were ones of reconstruction from a crushing defeat that were followed by an economic boom that rebuilt city centers and opened cultural institutions. In short order, Japanese post-war artists had a lot of material to react to and also had an enormous cultural legacy behind them.

Importantly, while nowadays Japanese artists are widely recognized, that was not always the case. It wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that a few Japanese contemporary artists, like Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara, made a splash on the international art market. And, as time went by, many private art collectors have become more interested in the work of previously unknown post-war Japanese artists, as reported by the following New York Times article. At the same time, during the last few years, a growing number of art exhibitions organized within the US and elsewhere have analyzed the legacy of Japanese avant-garde groups which go far beyond its borders. However, as Mika Maruyama voiced in an Artsy article, there is still a long road to cover in terms of scholarly research and on the promotion of Japanese artists other than the six “Star Artists of Japanese art”—Yayoi Kusama, Lee Ufan, Tatsuo Miyajima, Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, and Hiroshi Sugimoto.

Below we mention only a handful of the many art movements that redefined the development of Japanese post-war art.

Gutai: favoring large-scale multimedia and performance art

During the 1950s the radical Gutai Group favored large-scale multimedia and performance art. The Gutai Art Association was founded by the artist, critic, and teacher Jiro Yoshihara in 1954, and became one of the most influential avant-garde art groups. Initially composed of 16 members, by 1972 it had signed on more than 59 artists. As stated in the article The movements that shaped Japanese post-war art, Yoshihara challenged artists to expand the definition of art by doing radical art in which unconventional objects and actions, like light bulbs or body parts, were invited to the medium of painting. Some of Yoshirara’s most iconic practices were shooting paint onto a canvas with a cannon and plunging through laminated rice-paper screens.

"It is possible to view Gutai paintings as works emancipated from all restraints associated with modern art, and with a kinship to their contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Robert Rauschenberg."

Hajime Nariai

Notably, as explained by ARTnews, Gutai’s artists established bonds with many Western artists which in turn influenced other art movements such as Art Informel, a term coined by French critic Michel Tapié that described various styles of abstract painting that were gestural and anarchic. The latter has made art historians rethink the role of Japanese contemporary art as derivative given that many of Gutai’s experimental manifestations, preceded or occurred simultaneously with their European counterparts. For this reason, Alan Karpow has described Gutai artists as the precursors of Happenings. Important Gutai artists include artists such as Akira Kanayama, Atsuko Tanaka, Kazuo Shiraga, Saburo Murakami, Shozo Shimamoto, Michio Yoshiwara, and Sadamasa Motonaga.

Mono-ha: uncovering world’s mysteries

Created in 1968 and dissolved in the early 1970s, Mono-ha had a long-lasting influence on Japanese contemporary art. Mono-ha can be thought of as a tendency of loosely interconnected artists, unintentionally coinciding with Minimalism and Arte Povera, whose main goal is to attempt to touch the intrinsic mystery of the world with no distinctions between objects and situations, as stated by Hajime Nariai in the following essay. In this way, its members, mainly Lee Ufan, Nobuo Sekine, Katsuro Yoshida, Katsuhiko Narita, Shingo Honda, Susumu Koshimizu, and Kishio Suga, used natural materials, such as wood, stone, and water, to create minimal and often ephemeral artistic expressions. For example, Lee Ufan placed rocks on broken glass, or Kishio leaned square pieces of timber against architecture.

"Mono-ha artists were dealing with a fundamental reevaluation of what art is and what material is."

Mika Yoshitake

One of the main goals of this movement was to create contemporary Asian art free of what the artists considered to be their country’s growing absorption of international modernism. Aligning with an anti-materialistic and conceptual ethos, many Mono-ha artists made works meant to deteriorate or be destroyed. However, as explained by Shigeo Chiba in an Art Forum article, unlike earthworks and land art, which approached nature with assumptions based on art conceptions, the Mono-ha art artists were not concerned if their works were thought of as art and focused on their involvement with the world in itself.

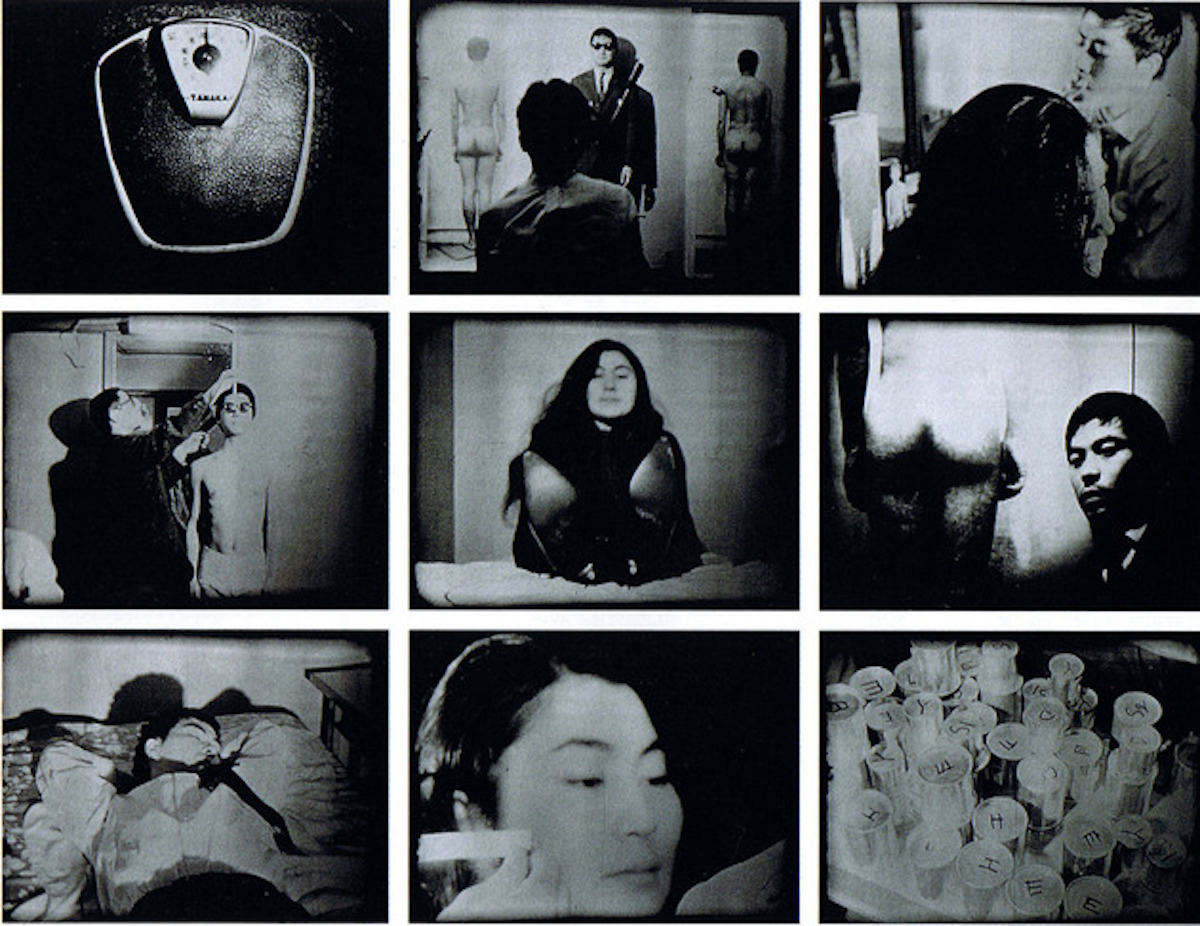

Tokyo Fluxus: process-driven works

Fluxus, which was also active in New York City and West Germany since 1961, also encompassed a good number of Japanese artists like Yoko Ono, Takako Saito, and Ay-O. As analyzed by Midori Yoshimoto in this post from MOMA, during these years, Japanese artists traveled often to New York and were also in correspondence with New York artists which resulted in linked vanguard communities. Particularly, Yoko Ono and Ichiyanagi Toshi (married from 1956 to 1962) were key figures in the forging of ties between artists in New York City and Tokyo which surpassed Fluxus boundaries.

In broad terms, international in its scope, Fluxus sought to challenge the ideas of art by focusing on the process rather than the final result. At the same time, Fluxus had a philosophy of making art accessible to all. After 1970, the collective activities of Fluxus decreased, but Japanese artists remained engaged with the movement. For example, Shigeko Kubota (a pioneer of video art and a Fluxus artist) and Nam June Paik (Fluxus member and video artist-Korean but grew up in Japan), who married in 1965, were close friends with George Maciunas, a founding member of the Fluxus movement.

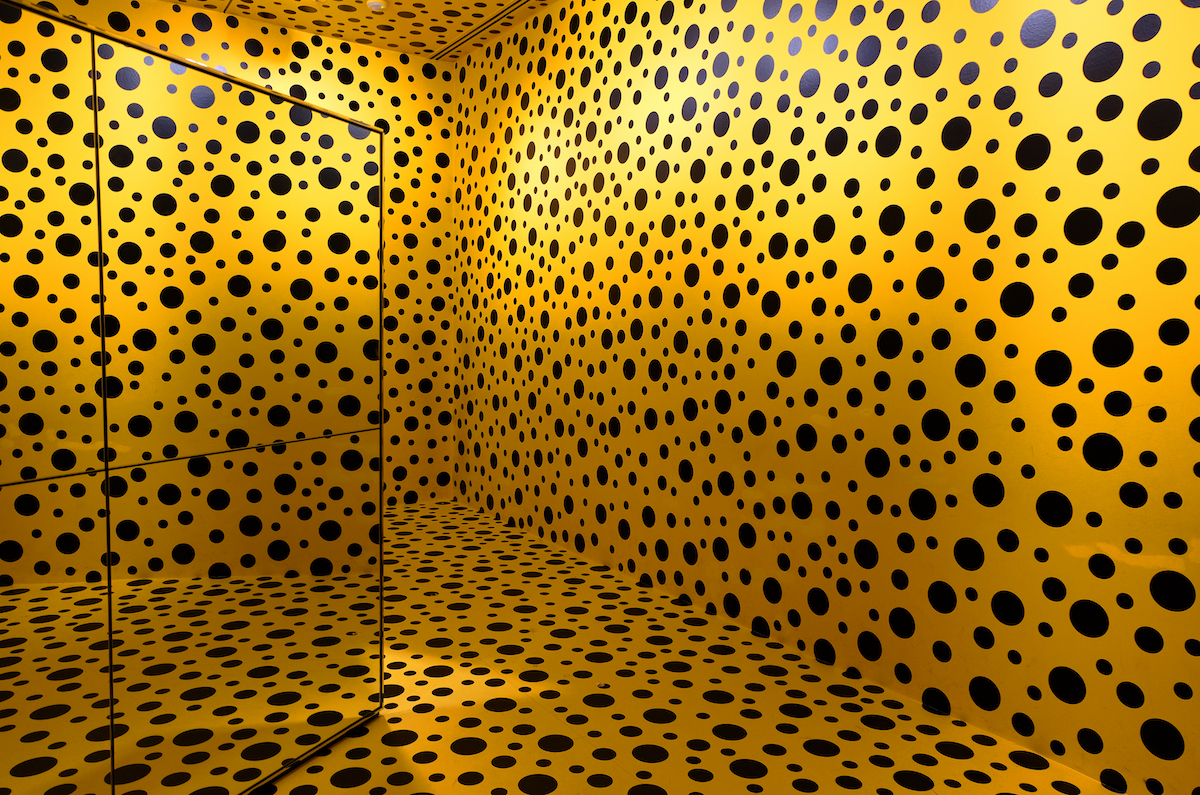

Obsessional artists: endless repetition

Active during the 1960s, the so-called obsessional artists created works connected to fantasies of fragmentation and endless repetition as a way of altering the significance of objects and creating new meanings. Particularly Yayoi Kusama, Miki Tomio, and Kudo Tetsumi were preoccupied with thoughts of the void. World-famous artist Yayoi Kusama, for example, became interested in dots, which are endlessly repeated across canvases, sculptures, and, eventually, entire rooms. “I am an obsessional artist,” she once said “People may call me otherwise, but…I consider myself a heretic of the art world.” On the other hand, as described by this Christie's article, artist Tomio Miki produced works populated by ears reproduced in different sizes and arrangements.

While these artists saw themselves as autonomous and were inspired by their personal backgrounds and the ever-changing context in which they lived, they were also influenced by other art trends. At the same time, their work was also closely followed by Western artists given Yayoi’s and Kudo Tetsumi’s moves to New York and Paris respectively which put them in direct contact with the art community, explained Clairy Estes in this article.

Superflat: a Japanese contemporary art movement

Often regarded as “Japanese Pop Art,” the term Superflat was coined by Takashi Murakami as a means to describe art forms based on the centuries-long Japanese "flat" art aesthetics characterized by bold outlines, flat coloring, and a lack of natural perspective, depth, and three-dimensionality. This “flat” aesthetic has permeated a myriad of Japanese art movements and styles with one of the most famous being ukiyo-e, the woodblock prints of the Edo period. Next to Japanese art forms, Superflat is also inspired by the country’s attraction towards anime and manga after World War II. More so, the term flat also comments on the flat and shallow nature of consumer culture which it has been said to either celebrate or critically exploit. While encompassing traditional art mediums, as explained in this profile of the artist, Superflat has also been connected to films, digital art, fashion, and interior design.

While coined in the 21st century the aesthetic behind Superflat was created decades before. As proof of this, in 1989, Murakami founded the Hiropon Factory in Tokyo, a creative workshop that emulated Andy Warhol's famous Pop art Factory and hiropon, a name for the methamphetamines available over the counter during World War II. Notably, in 2001, the same year Superflat was launched internationally, Murakami reconfigured the Hiropon Factory as a commercial company called KaiKai Kiki Co. Ltd, which employs artists to produce a myriad of artworks and objects for himself and other artists in the collective. As art critic Christopher Knight once noted, "Murakami is the first major artist, Eastern or Western, to make our pervasive culture of branding a primary subject."

"World War II was always my theme - I was always thinking about how the culture reinvented itself after the war."

Takashi Murakami

The art movements we have mentioned above cover a fraction of the many artists that shaped the many faces contemporary Japanese art has today. As time has gone by, many other young Japanese artists have continued to question their status quo through innovative and powerful visual languages. For example, artists like Yutaka Sone, Yuko Mohri, Chiharu Shiota, Yurie Nagashima Yasumasa Morimura, Chikako Yamashiro, and Meiro Koizumi were all included in Artsy’s list of 10 Japanese Artists Who Are Shaping Contemporary Art. We will cover them in future posts, but for now, it is safe to say Japanese art history is still being written as the art world is starting to give Japanese post-war artists their rightful place in art history.