The contemporary story of art collecting: the 20th and 21st centuries

For the last two-hundred years, the practice of collecting art has grown to unimaginable heights. As time has gone by, the art world has gotten more complex. Motivations behind collecting have oscillated between the love of art and a well-thought-out investment strategy for the future. Over the last centuries, the art community has evolved into a machine encompassing art dealers, art fairs, galleries, art advisors, artists, and many others aimed at helping collectors acquire the right piece at the right price. Importantly, the technological tools available have also brought an immediacy to the process of acquiring new pieces. Not to mention the effect that globalization has had on introducing collectors to artists that would otherwise be inaccessible.

What are the main characteristics of collecting art? and How have events over the last two hundred years shaped its history? In this two part series, we have explored how collecting art has become a passion experienced by millions around the world and how this passion has evolved into a powerhouse that generates billions every year. The first section covered the story of collecting art, while the latter is focused on answering questions outlined in the first article. As any art historian will tell you, we acknowledge that each of the following episodes is far more complex than a single blog post can cover. This is why we implore our readers to dive further into the topics.

From the first years of the 20th century to World War II

In the latter half of the 19th century, we saw a consolidation of private art collections by wealthy individuals. This consolidation paved the way for private museums and public institutions to open their doors to the public. For instance, in New York City we have the Frick Collection, which opened its doors in 1935 with the estate of Henry Clay Frick, a wealthy industrialist from Pittsburgh who made his money manufacturing coke for the steel industry. Aside from its many masterpieces, the collection is important because it houses the Center for the History of Collecting, an organization created in 2007 to support the study of fine and decorative art collections, both public and private, in Europe and the United States from the Renaissance to the present day.

The arrival of World War II bared consequences on the practice of collecting art. Many artworks were either relocated, stolen, or destroyed. Not to mention the implications of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), a Nazi organization tasked with seizing artwork from private Jewish collections, which is still being resolved today. An emblematic scene from this period was the recovery of artworks stored by Nazi’s in a salt mine in Altaussee, Austria. In other countries, like England, the most important art collections -such as the National Gallery one- were hidden in undisclosed locations. While chaos brewed in Europe, the art scene transitioned from Paris to New York City, which is where our story goes from here.

From the post-war period to the rise of art dealers

As the art world recovered in the postwar era, art dealers became increasingly influential in building art collections. Characters like Leo Castelli, an Italian-born art dealer, were pivotal in the creation of the contemporary art market. At a small gallery on 9th street in New York City, Leo Castelli brought to light many artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and many others. His legacy continues to this day in the form of the Leo Castelli Gallery (New York City), and more importantly, in the form of an archive, bequeathed to the Archives of American Art, that allows researchers to trace the history of art collecting during the 20th century.

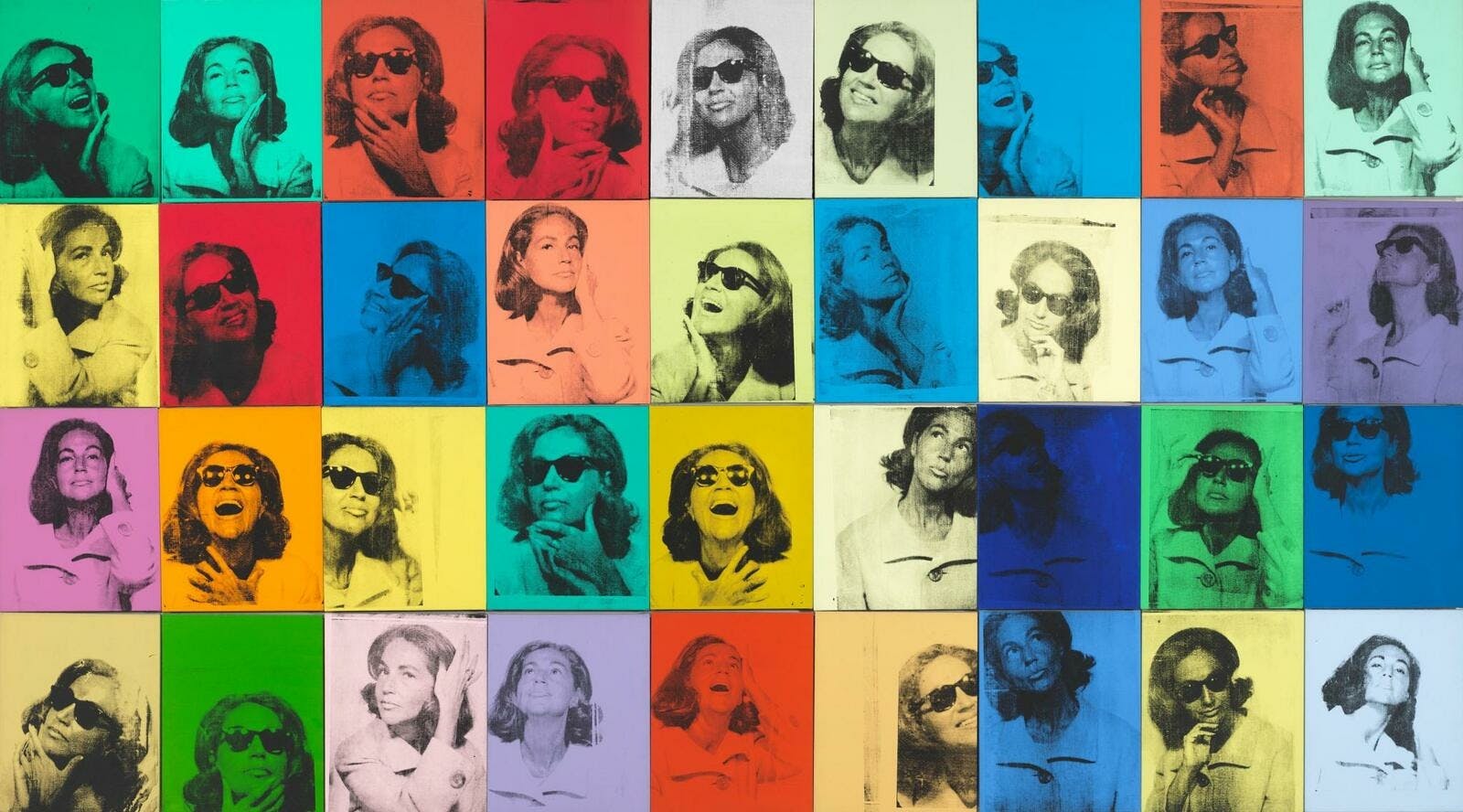

Aside from Leo Castelli, other relevant characters include Robert and Ethel Scull, two collectors who were instrumental in rethinking the art market and the creation of the contemporary art boom. In 1973 they single-handedly put together an emblematic auction showcasing work from their personal art collection, which encompassed works by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombley, Franz Kline, Frank Stella, and many others. The auction was an extreme success realizing a then-unheard of $2.2 million, or just under $12 million in today’s dollars. Furthermore, it brought together two ideas for collecting, 1) a sincere appreciation for art and 2) a keen eye for obtaining profits resulting in art as an investment. Interestingly, the Scull´s collection was temporarily brought back to life in 2010 with an exhibition organized by Acquavella Galleries (New York City).

The art market boom and the victory of contemporary art

The 1980s saw the rise of record sales including the buying of French impressionists and post-impressionists’ artworks by Japanese collectors. As stated by Takato Hiraki in the paper How Did Japanese Investments Influence International Art Prices?, this period in time is known as the “Japanese Bubble’, which unfortunately came to an end with the bubble bursting in the 1990s. As the decade came to an end, the art market was again revitalized as collectors pursued contemporary art more than the old masters of previous generations. Even if this trend was once perceived as temporary, it is very much alive today.

Resulting from this art boom, the 1990s saw the consolidation of distribution channels including powerful galleries with global reach, art fairs, and digital tools like artnet that led to the democratization of the art market. Besides, this era saw the flourishing of art advisors as a key role in providing access to the art market, sometimes educating clients, and assisting as an intermediary for art sales. This era also gave rise to the East-Asian art collector base as witnessed in the opening of Art Basel Hong Kong in 2013.

Trends in art collecting

For centuries art collectors have been driven by a set of diverse motivations, but in the last three decades, we’ve seen the growth of systematized practices that have given rise to trends in the art market. Among this scenery, one of the most important collecting trends has been to lend or donate artworks to museums. This is evident in the fact that, according to the Association of Art Museum Directors, more than 90% of art collections held in public trusts by American museums were donated by private individuals.

Another trend that is worth mentioning is the rise in artists becoming avid collectors themselves; frequently trading their own work as for new artworks. While this trend isn’t anything new, we’ve definitely seen an increase in it over the past two decades. For example, Monet and Picasso each built extensive collections with the one once owned by Monet being temporarily exhibited at the Musée Marmottan in Paris. Besides, in 2015, an exhibition was mounted at the Barbican, in London, exploring the art collections of 14 contemporary artists. Sol Lewitt was one of the featured artists, whose collection comprised more than 7000 artworks ranging from Japanese woodblock prints to contemporary artworks. Adding on, one of the highest-selling artists of our time, Jeff Koons, also owns an art collection ranging from old masters to contemporary art which, according to a New York Times article by Linda Yablonsky, are linked by their underlying sexual references. Another great collection is that of Brian Donnely, more commonly known as KAWS. His collection encompasses work by George Condo, Martin Wong, Joyce Pensato, Keith Haring, Peter Saul, and many others.

Perhaps, one of the main trends in art collecting is the rise of private art museums and exhibition spaces. As stated in The Private Art Museum Report released in 2015, 71% of the world’s private contemporary art museums were founded in the last 15 years. This report examines the global rise of private museums based on data from 317 museums in 45 countries. Occupying the top 5 ranks are South Korea, the United States, Germany, China, and Italy. This ranking is further evidence of the growing East-Asian art market. Furthermore, Dr. Christine Howald, one of the authors of the report, asserts that “the boom in private art museums shows that private art collectors are not the keepers of a closed system for the elites anymore but take over responsibility for making art accessible to everyone.” When talking about this topic we also need to remember that many countries offer tax deductions and exemptions to further motivate this type of behavior.

As a corollary to this ongoing story, we cannot help but talk about the current pandemic and how it has affected the art market; shifting it to a digital realm where art fairs, art negotiations, and art trades are now taking place online. However, as museums, galleries, auction houses, and institutions begin to reopen, we’ll have to see how the art market evolves. Will art museums start to reopen? Will art collectors be cautious? Or will collectors resume their usual routines? Without a doubt, it will still take time to reckon the quantitative and qualitative effects that this pandemic has had on the global art market and the many institutions that rely on philanthropic collectors to fund their annual budgets. We will keep you posted as this story evolves.