Elmyr de Hory: Fiction and facts surrounding the life of a world-famous art forger

Why are we always captivated by the lives of con artists? From popular novels to blockbuster hits and binge worthy Netflix series, con artists of all kinds populate the realms of storytelling. Within the art world, while the actions of art forgers and scammers have had awful consequences, their lives attract our attention and, more often than not, their abilities and wit are secretly amaze us. Such is the case with Elmyr de Hory, one of the most prolific art forgers of modern times, who during the 1950s and 1960s faked more than 1000 artworks, some of which still hang on museum walls around the world. This article covers the story of de Hory’s life and explains how he managed to turn his life into that of a legend.

Fiction and facts surrounding Elmyr de Hory’s life

As is the case with many conmen, Elmyr de Hory changed his name and constructed a fictionalized identity, which contributed to his allure and granted him access to the art world elite. Only until recently, have we become aware of the facts surrounding his life which we will delve into below.

Before we get started, let’s cover the basics of his life. Elmyr de Hory was born in 1906 as Elemér Hoffmann (no one knows when he changed his name to Elmyr de Hory) to lower-middle-class Jewish parents in Budapest, Hungary. Contrary to other art forgers, such as Wolfgang Beltracchi, de Hory was formally trained as a visual artist. He studied in the Hungarian art colony of Nagybánya at the age of 16, went to the Akademie Heinmann art school in Munich, and then went to the Académie la Grande Chaumière in Paris in 1926, where he allegedly studied under the world-famous artist Fernand Léger, as reported by Widewalls. However, as the The New York Times explained, no one knows how he financed his studies or if he really attended all those schools. Regardless of the extent of his education, de Hory’s approach to painting was reminiscent of Post Impressionism and was not aligned with the more abstract or conceptual trends of his time.

During his time in Europe, de Hory was no stranger to crime. He was convicted ten times in five European cities (between 1927 and 1931) for crimes including check fraud, counterfeiting documents, and falsely claiming an aristocratic title. His encounters with the law showcased his knowledge of financial sectors, which helped him with future endeavors of art fraud. Interestingly, his whereabouts from 1939 to 1949 remain unknown. de Hory frequently claimed that he was imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps and that his whole family had been killed by the Nazis, but ultimately this has been discredited by researchers who discovered one of his siblings.

De Hory’s forgery enterprise thrives

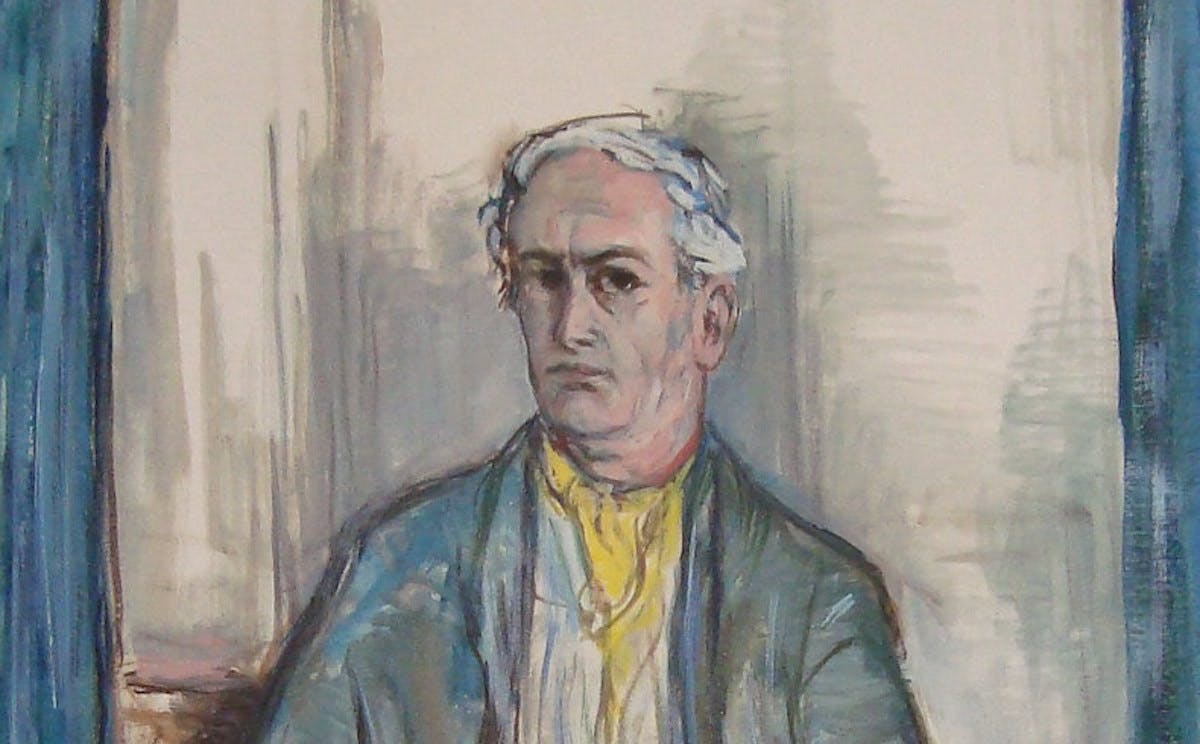

Regardless of how de Hory passed the years of the war, it is believed that he returned to Paris in 1946, where he first started to forge artworks after Lady Malcolm Campbell saw one of his drawings and thought it was a Picasso. Following his time in Europe, de Hory moved to the United States in 1947 and tried to make it as a fine artist, but ultimately failed. Nonetheless, during this time, de Hory continued to sell fakes to anyone interested in buying them. It is at this point in his life that de Hory starts to develop the fictitious life he is known for. To sell his works de Hory created a fake identity and impersonated a Hungarian aristocrat, with no Jewish ties, who had fallen on hard times after the war and who owned a collection of high-quality artworks that he was eager to sell to get by. Jeffrey Taylor recounted that, as part of his cover as a member of the European elite,de Hory often displayed a portrait of himself and one of his brothers in sailor suits allegedly painted by the famous Hungarian portraitist Philip de László, but in reality was painted by him.

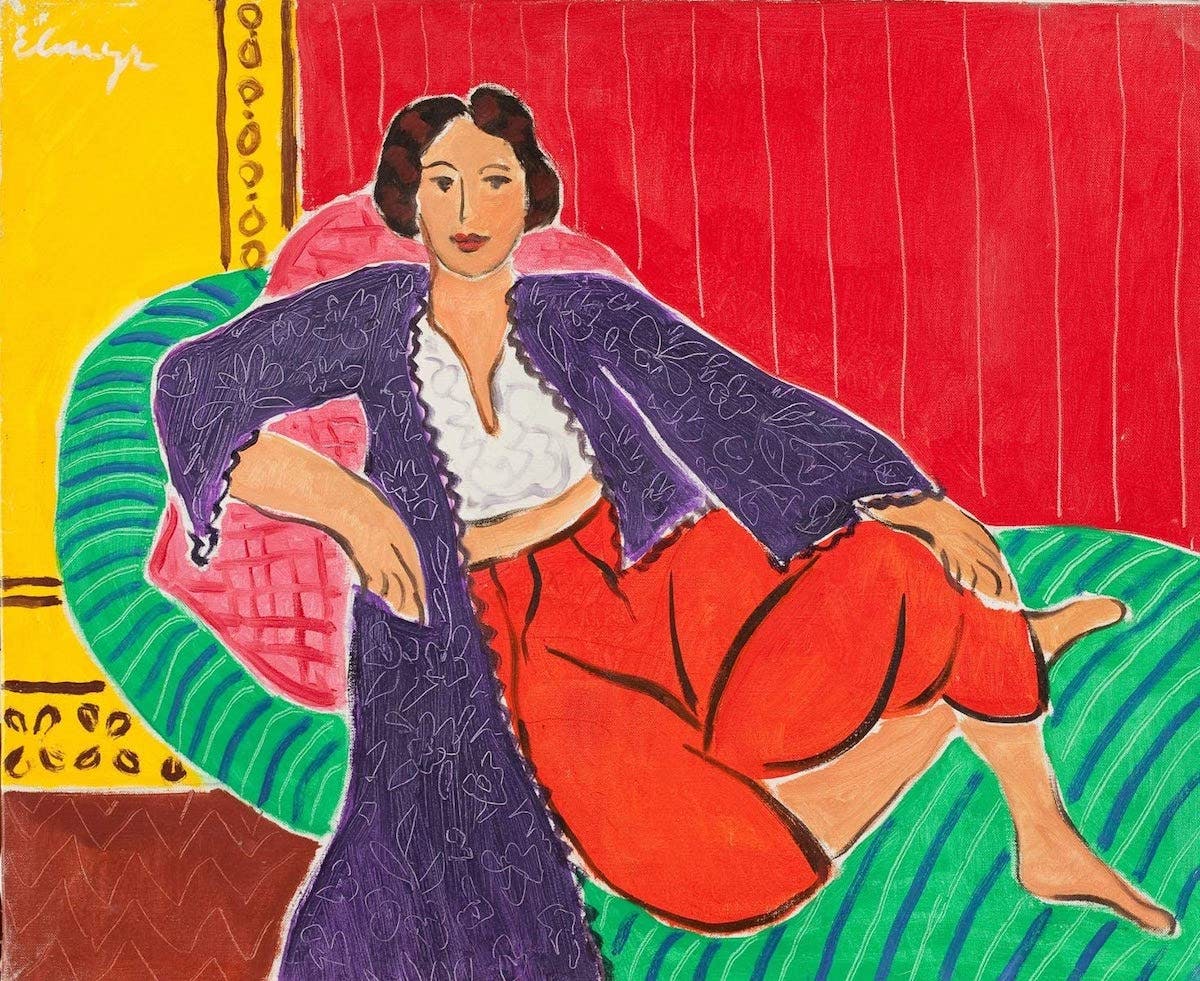

Under the identity of impersonated European aristocrats, de Hory sold forgeries that mimicked the styles of famous artists who were still alive, like Picasso and Matisse, and also created countless forgeries of Amedeo Modigliani. As a matter of fact, as Kenneth Wayne (director of The Modigliani Project) shared with The New York Times, de Hory produced so many Modigliani forgeries that it is almost impossible to create a definitive catalog ofModigliani’s work.

To get a glimpse of the scale of de Hory’s scam, during his time in the United States, de Hory’s works were bought by reputable art galleries such as Niveau Gallery and the now disgraced and defunct Knoedler & Co in New York, who acquired fake Modiglianis. At the same time, art museums also purchased the fakes. For example, he sold a forged Matisse to the Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, and a fake Picasso to the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, both in Kansas City. Unfortunately, there is no such thing as an inventory of de Hory’s fakes, which makes it impossible to know the whereabouts of his forgeries and how many exist.

De Hory’s forging technique

How exactly did de Hory manage to trick the eyes of so many art experts around the world? First of all, for more than ten years, de Hory largely faked works on paper since it was easier to give paper an aged appearance simply by brushing it with tea and, as Jeffrey Taylor stated in an essay, drawings on paper were also a good option given that many of the artists he was forging, like Picasso and Matisse, were still alive and might hear about new paintings on canvas, as opposed to lower-priced drawings on paper. This approach led him to also produce fake lithographs.

However, after some time, de Hory started to work with canvases presumably because of the higher profits. To create a forged canvas, he would usually obtain old canvases (frequently from the nineteenth century) from the Paris flea markets, and would scrape off the paint carefully leaving the grounding intact. He would then paint the image and bake it to dry the oil paint after applying materials like Vernis à craqueleur, a varnish that produces a quick craquelure; and Vernis à vieillir, which imparts a rich golden-aged hue on top of them. Importantly, de Hory did not give much attention to the dates and characteristics of specific pigments used by the artists he was forging. This fact is important, since forensic studies of artworks hadn’t yet developed. Like many other forgers, the wrong pigments are what eventually gets them caught.

De Hory’s downfall

During the early 1950s,de Hory’s forgeries started to raise eyebrows, and an FBI investigation was opened to look into the many claims that he was selling fakes. While at risk of getting caught, and already under the radar of authorities, in 1958 de Hory began a business partnership with Fernand LeGros, an art dealer in New York, who began selling hand-drawn “lithographs” and other forged works by de Hory. LeGros and other art dealers would create fake provenance records and come up with all sorts of tricks to deceive collectors and art world authorities, such as inserting photographic copies of de Hory’s works into auction catalogs and artist monographs. They were also very knowledgeable on who they could bribe and who they could fool.

However, due to the growing interest from authorities, de Hory fled to Ibiza, where he was briefly incarcerated for homosexuality. During this time, LeGros continued the “business partnership” from Paris and lived extravagantly from the inequitable distribution of profits, as described on the Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World website. When it was later discovered that Le Gros had sold forty forged paintings to the Texas oil millionaire, Algur Meadows, Le Gros clung to his sanity and issued a myriad of counter lawsuits and accusations.

Importantly, upon his arrival to Spain, de Hory let go of his fake identity and decided to make his life story as an art forger known to the world. With this idea in mind, he even teamed up with the novelist Clifford Irving (1930-2017), who later on wrote a fake authorized biography of Howard Hughes, to write his best-selling biography Fake! (1969). Fittingly enough, Irving told de Hory’s version of the story including countless exaggerations and inventions. His life was also covered by the Orson Welles’s film F is for Fake and has been explored in many other books and documentaries, such as Real Fake: The Art, Life & Crimes of Elmyr de Hory.

Perpetuating the legend of Elmyr de Hory

In 1969, during his time in Spain, de Hory met then 20-year-old Mark Forgy on the beaches of Ibiza. According to Forgy, de Hory employed him in different positions, painted many portraits of him, and shared his knowledge of the art world and professional, aristocratic etiquette. However, their friendship came to an end in 1976, when de Hory killed himself after learning he would be extradited to France to face his accusers.

In his will, de Hory left everything to Forgy, who later returned to the US with hundreds of forged works and who until 2007 decided to begin a memoir which he self-published in 2012. Over the years, Forgy also created a website where he promotes ventures devoted to studying the life and work of de Hory.Next to the buzz surrounding de Hory’s life,Forgy’s version of the story garnered the attention of the public and, as explained by The New York Times, has created a demand for faked works by de Hory.

Importantly, as evidenced by the many art exhibitions celebrating famed art forgers and their crimes, Forgy is not the only one interested in de Hory’s work. For example, in 2013, the aforementioned touring exhibition Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World, which started at the Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, Massachusetts, included de Hory’s paintings next to the works of other famous forgers. Colette Loll, the exhibition’s curator and an art investigator who organized the exhibition with the nonprofit group International Arts & Artists, said to The New York Times, “What links these men are “frustrated artistic ambitions, chaotic personal lives and a contempt for the art market and its experts.”

Recently, Forgy himself organized an art exhibition displaying the many portraits that de Hory painted during his time in Ibiza. Some of the artworks displayed at the Hillstrom Museum of Art are unfinished or pulled from de Hory’s sketchbook. The works showcase a myriad of art styles and seem almost like an inventory of the many influences de Hory had while forging famous artists.While nowadays more facts continue to emerge about de Hory and his forgeries have been subjected to rigorous lab analysis that has identified his forging method, his legend continues to be nourished by our love of art scandals.